Relative Directories for Better Project Organization

But my phone just organizes everything for me…

Nowadays, with all our mobile devices, many of us are used to downloading everything into a single downloads folder, then perhaps just searching for the file we want. And when we switch to our laptops, this might translate to downloading, or saving all our work directly onto the desktop. And that work great for work for occasional file access, but it’s a poor strategy for managing a structured project. Especially when we have data, and code, and reports to organize.

Here we will take a look at how to effectively use folders to organize our files. And how to use relative paths to access those files in code without hardcoding full file paths.

What’s wrong with using Downloads?

It works fine, right? Well, kind of. For certain simple use-cases. But there are some limitations in a project scenario.

- Hard to find specific files, especially if you downloaded them a while ago.

- Files are not grouped, so files from different projects end up lumped together.

- Scripts break if the file structure changes. This is a biggie

- Paths change from one computer to another - also a biggie! More on this in a minute!

What’s wrong with using Desktop?

All the same issues as using Downloads! It’s, still a dumping ground. It’s just a different pile. Plus, its worth noting that on some systems, especially those with cloud sync tools like OneDrive or iCloud, the Desktop folder might be constantly syncing. This can slow down read/write operations, especially for large datasets or frequent file updates.

Note that it is fine to use a cloud storage solution. Just don’t have it syncing with your desktop.

Using a dedicated local project folder (e.g., in Documents or a separate Projects directory) avoids this and keeps things running smoothly. And this is what we will be looking at going forward.

Project structure

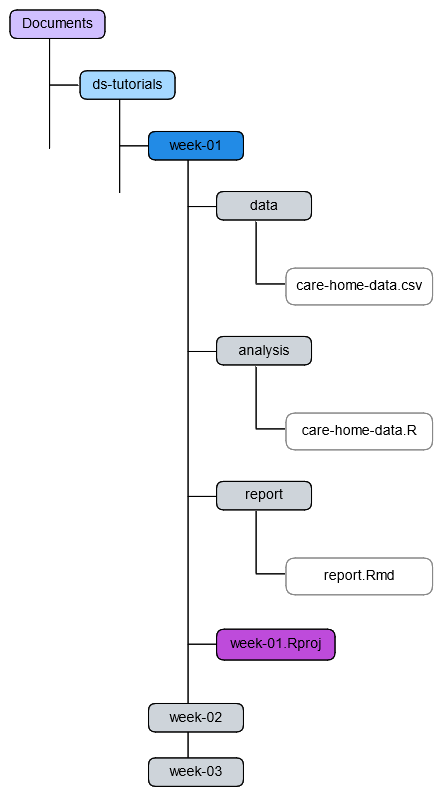

For the following, imagine we have a project that looks like this

File paths

As the name suggest a path is like a set of directions that specify where a particular resource can be found. For example, you could have two files with the same name, and as long as they live at different locations, there is no problem. The file path gives directions to find the specific file you need. A path is composed of a list of directories (dirs) separated by slashes /.

For example the below shows two files called file.docx, that both live in the same project, but one is in the temp-work/ dir, and the other is in real-work/

C:\Users\your-name\Documents\project\temp-work\file.docx

C:\Users\your-name\Documents\project\real-work\file.docx

For the purposes of this document, any time we are considering a directory, I will try and suffix it with a / to distinguish it from files, which I will always try to ensure end with a dot followed by three or four letters, e.g. file.txt, file .docx, etc.

Absolute paths

An absolute path is “absolute” in the sense that it points to a completely unique and unambiguous location - which seems like it should be a good thing, right?. They usually start with something like C:\ on Windows or /Users/ on Mac - i.e the root folder of your disk.

Suppose you have an analysis script that lives in the analysis dir as seen in Figure 1. Then the absolute path to that script might be

C:/Users/your-name/Documents/ds-tutorials/week-01/analysis/analysis.R

And this script uses a file called data.csv. If a path starts at the root, then the rest of the path will look something like

C:/Users/your-name/Documents/ds-tutorials/data/data.csv

Note that the paths contain your-name. If you choose to only ever work with people with the same name as you, probably not a problem. But if you share your project will anyone else…

- That path is only guaranteed to work on your specific computer.

- If your username changes, or if you move your project, the path breaks.

- If you send the project to someone else, it definitely breaks.

- If you even have two computers, and each has a different username, you won’t be able to find your own work!

Even on your own machine, moving a folder from Desktop to Documents can invalidate a dozen file references in your code.

So, absolute paths are “brittle”.

- Great for pointing at static stuff (that never leaves your current device).

- Not so great for portable / shareable projects.

Relative paths

In the real world, relative paths are like directions from where you are, not from the edge of the map.

Again look at Figure 1, and imagine how you might describe where to find the data to someone else that was physically stood on the analysis script. You might say something like “go up one directory, then go down into the data directory…”. And that is exactly how a relative path works. Instead of going all the way to C:/ it says “starting from here, go to…”. So, in code, we write the current directory using ./, and one directory up (the containing, or parent directory) using ../.

So inside our analysis script, we could construct a path that point to the data as so

../data/care-home-data.csv.

Now, when you share your work, as long as your collaborator has the whole project directory, they can place that director anywhere they like, and the path with still work.

The here package

Relative paths are great, and fairly fail safe. But actually, it can be difficult to keep track of what level you are at in the file structure. Imagine a script nested four dirs deep, looking for data nested somewhere else 6 dirs deep!

What if we could decide which dir was considered the “root” dir? So, instead of going all the way back to C:, we told R to consider the start of the current project to be the root directory?

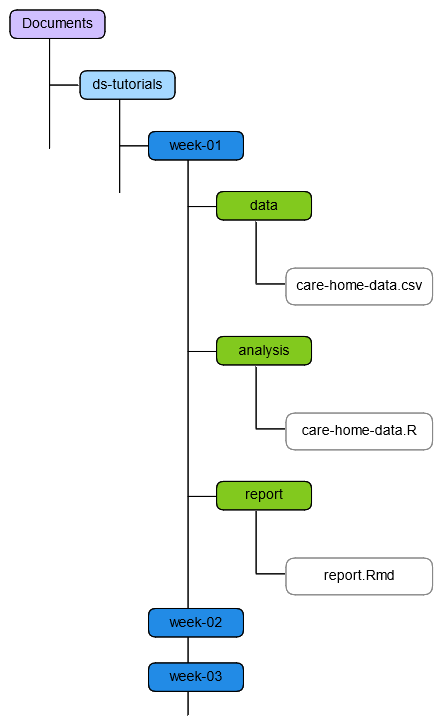

If you use RStudio projects, RStudio will place a file called project-name.Rproj inside the project’s top level directory. In our current case, the top level dir is `week-01 (Figure 2)

Using the here package basically “short cuts” the absolute path, based on the .Rproj file Instead of typing

C:/your-name/Documents/ds-tutorials/week-01/.../...

we can construct our paths starting from week-01, for example here::here('data', 'care-home-data.R'). Notice the use of ::.

This means we can use the here function from within the here package, without having to attach the package to our R environment (i.e. no need for library(here))

So we get the bonus of thinking about our paths only from the current project directory, but get the benefit of seeing the full, unique, and unambiguous location of the file we want to read.